Les collections du Mucem

Héritier du musée d’Ethnographie du Trocadéro et du musée national des Arts et traditions populaires, le Mucem oriente depuis 2005 la politique d’enrichissement de ses collections et fonds ethnographiques vers l’Europe et la Méditerranée.

Le Mucem met à votre disposition des informations issues des bases de gestion des collections, des archives, de la bibliothèque. Malgré un travail de documentation des collections permanent, certaines informations peuvent être encore incomplètes ou inexactes. Si vous remarquez des erreurs ou disposez d’informations complémentaires sur un objet, vous pouvez nous le signaler à contactccr@mucem.org.

Les images les plus anciennes sont de qualité variable, parfois réalisées uniquement à des fins d’identification des objets. Nous les remplaçons au fur et à mesure des campagnes de numérisation.

Découvrez les collections par thèmes

Les actualités des collections

Voir toutes les actualités

Restauration : Orchestrophone Limonaire

Le Mucem conserve une importante collection d’art forain témoignant de l’essor que connurent les foires et fêtes foraines aux XIXe et XXe siècles, dont cet orgue à 60 touches réalisé en 1903 à Paris par la manufacture Limonaire Frères. Restauré à l’occasion d’un prêt à la saline royale d’Arc-et-Senans pour l’exposition Destins de cirque (24 octobre 2020 – 9 janvier 2022), il est à (re)découvrir dans la réserve visitable du Centre de Conservation et de Ressources du Mucem à l’occasion des prochaines Journées européennes du patrimoine, ou des visites mensuelles proposées gratuitement au public.

Acquisition : le graffeur Sike

Take your place, SIKE, skaï, matière synthétique et métal peints à la bombe, crayon marqueur et crayon à bille, 2014, Toulouse.

Inv. n° 2022.6.1. Photo Mucem / Marianne Kuhn.En 2022, le Mucem a enrichi ses collections par l’acquisition d’œuvres, d’outils de création et d’archives photographiques du graffeur Sike. Cette acquisition prolonge l’enquête-collecte Graff & Hip-Hop, conduite depuis la fin des années 1990 par le musée national des Arts et Traditions populaires, dont le Mucem est l’héritier.

Entretien avec Pascal Laporte, agence Vezzoni

Pascal Laporte, architecte, diplômé de l’École d’architecture de Marseille, et de l’École supérieure d’arts appliqués Duperré (diplôme de plasticien option surface) est co-fondateur de l’agence Corinne Vezzoni & Associés.

En 2004, l’agence est choisie pour construire les réserves du Mucem : le Centre de Conservation et de Ressources, situé à la Belle de Mai, au 1 rue Clovis Hugues, ouvre ses portes en 2012. Dix ans plus tard, Pascal Laporte revient sur la conception de ce bâtiment.

Restauration : Vierge de l’Immaculée Conception

Restauration d’une peinture sous verre pour l’exposition « Une autre Italie »

Les expositions temporaires sont souvent l’occasion de restaurer des œuvres, pour les consolider en vue de leur déplacement, ou pour améliorer leur lisibilité. La peinture sous verre représentant l’Immaculée conception a ainsi fait l’objet d’une restauration pour l’exposition « Une autre Italie » (Fort Saint-Jean, du 25 mai au 10 octobre 2022), où elle fera partie d’un ensemble consacré à la piété populaire.

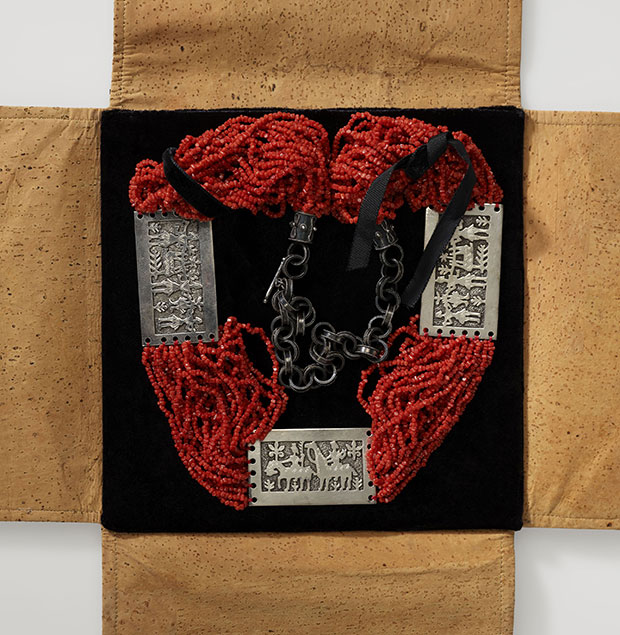

Acquisition : Ceinture I danzatori del crepuscolo (Les danseurs du crépuscule)

Comme prolongement de l’enquête-collecte sur le bijou en Méditerranée menée en 2018 en Sardaigne où l’orfèvrerie est riche d’influences multiples et où les artisans continuent à fabriquer des bijoux traditionnels, le Mucem a acquis en 2022 une création de Caterina Murino. Caterina Murino est une actrice sarde, célèbre notamment pour son rôle aux côtés de Daniel Craig alias James Bond dans Casino Royale (2006) mais elle est aussi créatrice de bijoux et fervente défenseure des savoir-faire des artisans de son île. Elle a ainsi imaginé une ceinture en argent filigrané et corail qui cristallise à elle seule toute l’identité de l’orfèvrerie sarde, entre tradition et création contemporaine. Pour dessiner les scènes des trois plaques en argent de la ceinture, Caterina Murino s’est inspirée des bronzetti, petites statuettes de l’ère nuragique trouvées lors de fouilles en Sardaigne et dont certaines sont conservées au Musée archéologique de Cagliari. Les animaux et les petits personnages présents sur ces scènes de chasse rappellent aussi ceux des tapis traditionnels sardes, les tapetti.

Acquisition : Ce Raoul LALA Là

Le Mucem et les marionnettes c’est une longue histoire d’amour. Les réserves du musée en regorgent. Depuis 2021, Raoul Lala, grâce au parcours connecté réalisé par M@riolab, propose de manière ludique de découvrir la collection de marionnettes du Mucem.

Pour fêter cette belle collaboration entre le musée et la célèbre marionnette marseillaise, le Mucem a décidé en 2022 d’acquérir Raoul Lala. Cyril Bourgois, l’auteur-marionnettiste de Raoul Lala a créé une copie de sa propre marionnette, au cours d’une résidence de 5 jours au Centre de Conservation et de Ressources du Mucem.

Mannequinage des costumes pour l'exposition « Fashion Folklore »

Les collections textiles du Mucem constituent le cœur de l’exposition « Fashion Folklore ». Les costumes populaires sont mis en regard avec des pièces de haute couture et de grands créateurs. Pour permettre ce dialogue, le mannequinage, c’est-à-dire l’installation des pièces sur des mannequins pour l’exposition, est une étape indispensable et une opération minutieuse.

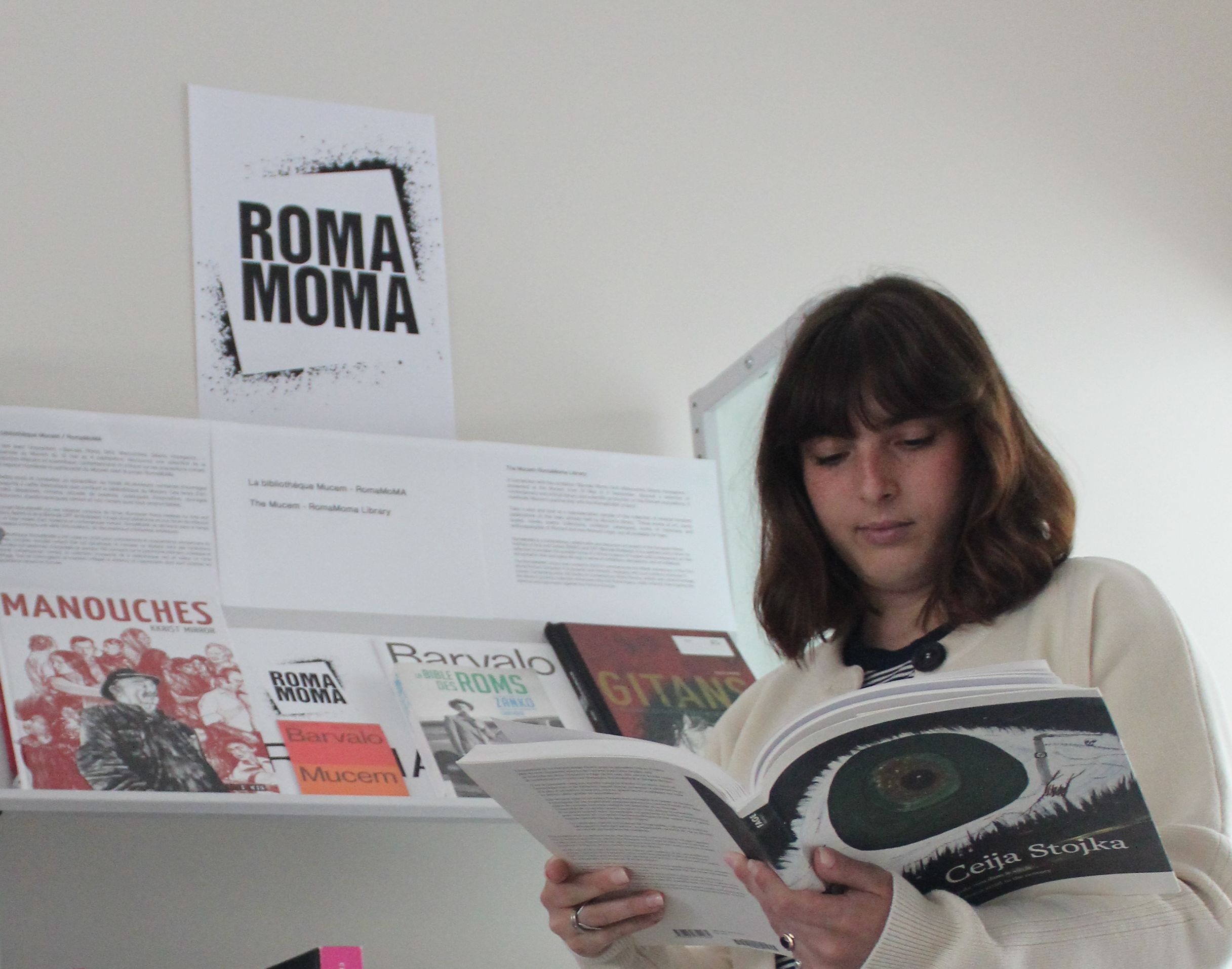

La bibliothèque Mucem / RomaMoMA

En lien avec l’exposition « Barvalo. Roms, Sinti, Manouches, Gitans, Voyageurs … » présentée au Mucem du 10 mai au 4 septembre, découvrez une sélection de la production littéraire et scientifique, contemporaine et critique sur les populations romani. Cet espace manifeste le partenariat du Mucem avec le projet RomaMoMa.

Le projet RomaMoMA est une initiative conjointe de l’Eriac (European Roma Institute for Arts and Culture, Berlin) et de la Biennale OFF de Budapest. Il s’agit d’une plateforme et d’un forum de réflexion sur un futur musée d’art moderne et contemporain romani. RomaMoMA se déclinera dans le temps et l’espace à travers une série d’expositions, de discussions et d’initiatives artistiques.

Restauration d'objets dans le cadre de l'exposition « Abd el-Kader »

Chaque exposition est l’occasion d’un regard plus précis sur les objets, pour assurer leur présentation dans de meilleures conditions.

Le pôle régie du Centre de Conservation et de Ressources du Mucem fait pour cela appel à des restaurateurs agréés par le Ministère de la culture.

Acquisition "Vierge à l'Enfant assise sur la Sainte Maison de Lorette"

La Sainte Maison de Nazareth, où la Vierge Marie aurait vécu et où elle aurait reçu l’Annonciation, était un important site de pèlerinage en Terre sainte au Moyen Âge. A la fin des croisades en 1291, il devient plus difficile pour les chrétiens d’Occident de s’y rendre : c’est alors qu’aurait eu lieu son transfert miraculeux jusqu’à Lorette, dans la région italienne des Marches.

Explorez par focus

Plongez dans l’immensité des collections du Mucem et voguez au gré des thèmes étonnants imaginés par nos conservateurs. Découvertes et dépaysement garantis !

Découvrir

DécouvrirTag et graff, un «art illégal» au musée

Entre 2001 et 2006, Claire Calogirou, chercheur associée a mené plusieurs enquêtes-collectes sur le thème du hip-hop, de la danse, du tag et du graff. Pour le graff, ce sont 958 objets qui ont été portés à l’inventaire du Mucem ce qui représente une étonnante collection de panneaux graffés, affiches, autocollants, marqueurs, bombe aérosol, magazines, esquisses, photographies, vidéos, etc. Cette enquête très riche permet une réflexion sur les rapports sociaux en milieu urbain, la question de l’appropriation de l’espace public et de sa conquête par des pratiques qui se revendiquent de la rue. Découvrir

DécouvrirFootball & identités

Une enquête-collecte méditerranéenne

L’enquête-collecte « Football & identités », représente 3 ans d’investigations, menées de 2014 à 2016, dans 10 pays de la zone méditerranéenne : Algérie, Bosnie-Herzégovine, Espagne, France, Israël, Italie, Maroc, Palestine, Tunisie et Turquie.

4 chercheurs en sciences humaines – Christian Bromberger, Abderrahim Bourkia, Sébastien Louis et Ljiljana Zeljkovic – accompagnés parfois d’un conservateur – Florent Molle – et de photographes – Giovanni Ambrosio et Yves Inchiermann – ont collecté plus de 400 objets, environ 3000 photographies et plus de 6h d’enregistrements vidéo. Les objets et photographies collectés doivent, à leur retour du terrain et après étude, être présentés dans les commissions d’acquisition du Mucem pour intégrer ou non les collections publiques et être mis à disposition du public. Découvrir

DécouvrirCélébrité!

Objets de culte et star system dans les collections du Mucem

Une robe, une console, une boucle de ceinture, un maillot de foot, une paire de chaussures, un maillot de bain, un poste de radio: voici l’énumération de simples objets du quotidien, témoins de leur époque. Cette liste n’aura pas le même impact si on y accole les noms des personnes auxquelles ils ont appartenu: la robe d’Edith Piaf, la console de mixage des Pink Floyd, la boucle de ceinture de saint Vincent Palotti, le maillot de foot de Cristiano Ronaldo, les chaussures de Mistinguett, le maillot de bain de Miss France, le «cataposte» de Psykose. D’anodins, ces objets se chargent de pouvoir, étincellent des feux de la célébrité. Ils en deviennent désirables et «magiques». Mais ces reliques ont un prix qui, lui aussi, est loin d’être anodin… Découvrir

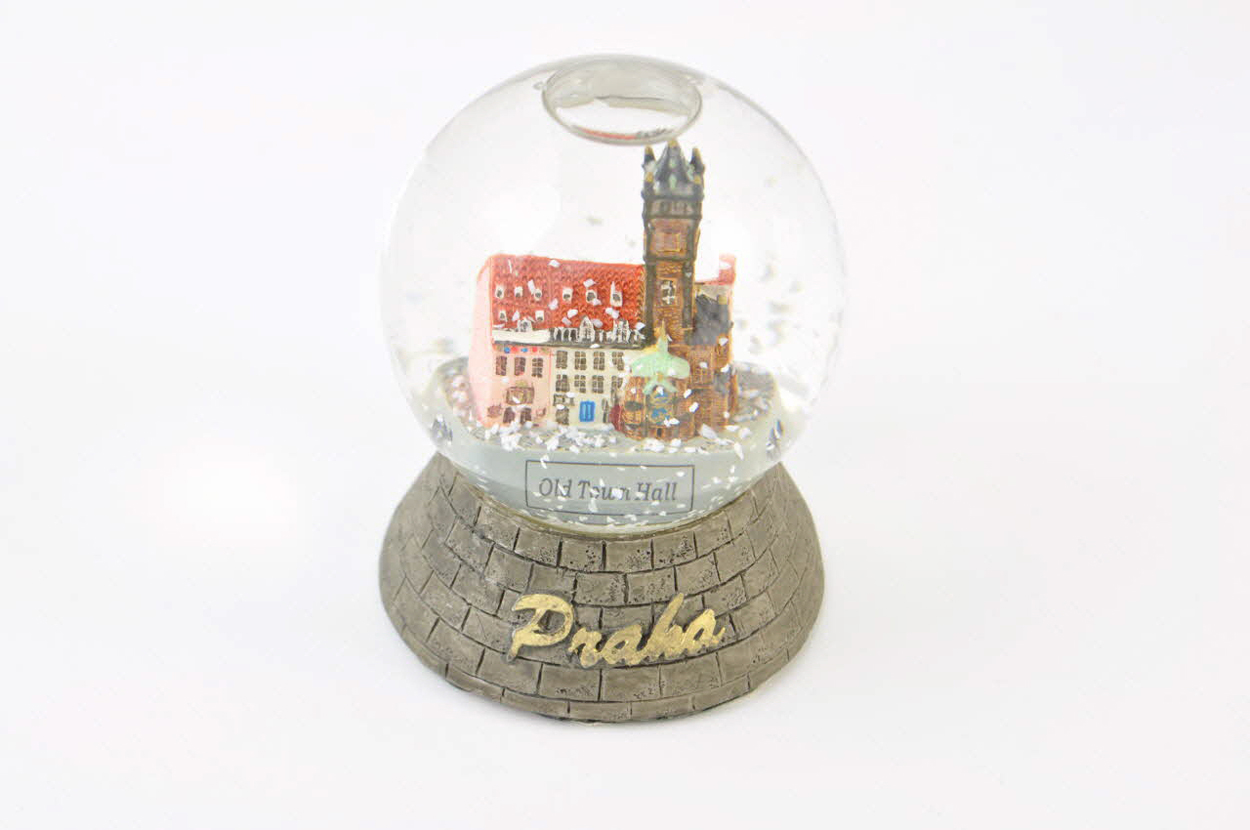

Découvrir«Vivre au temps du confinement», la collection

En avril 2020, le Mucem lançait une grande collecte participative autour de nos vies confinées. Vous avez été nombreux à y répondre.

Le Mucem a reçu plus de 600 propositions, encore à ce jour en cours d’analyse, et dont certaines entreront, à la fin du processus d’étude, dans ses collections. Un livret numérique recense l'ensemble des propositions que cet appel aura permis de collecter, et dont voici quelques exemples : Découvrir

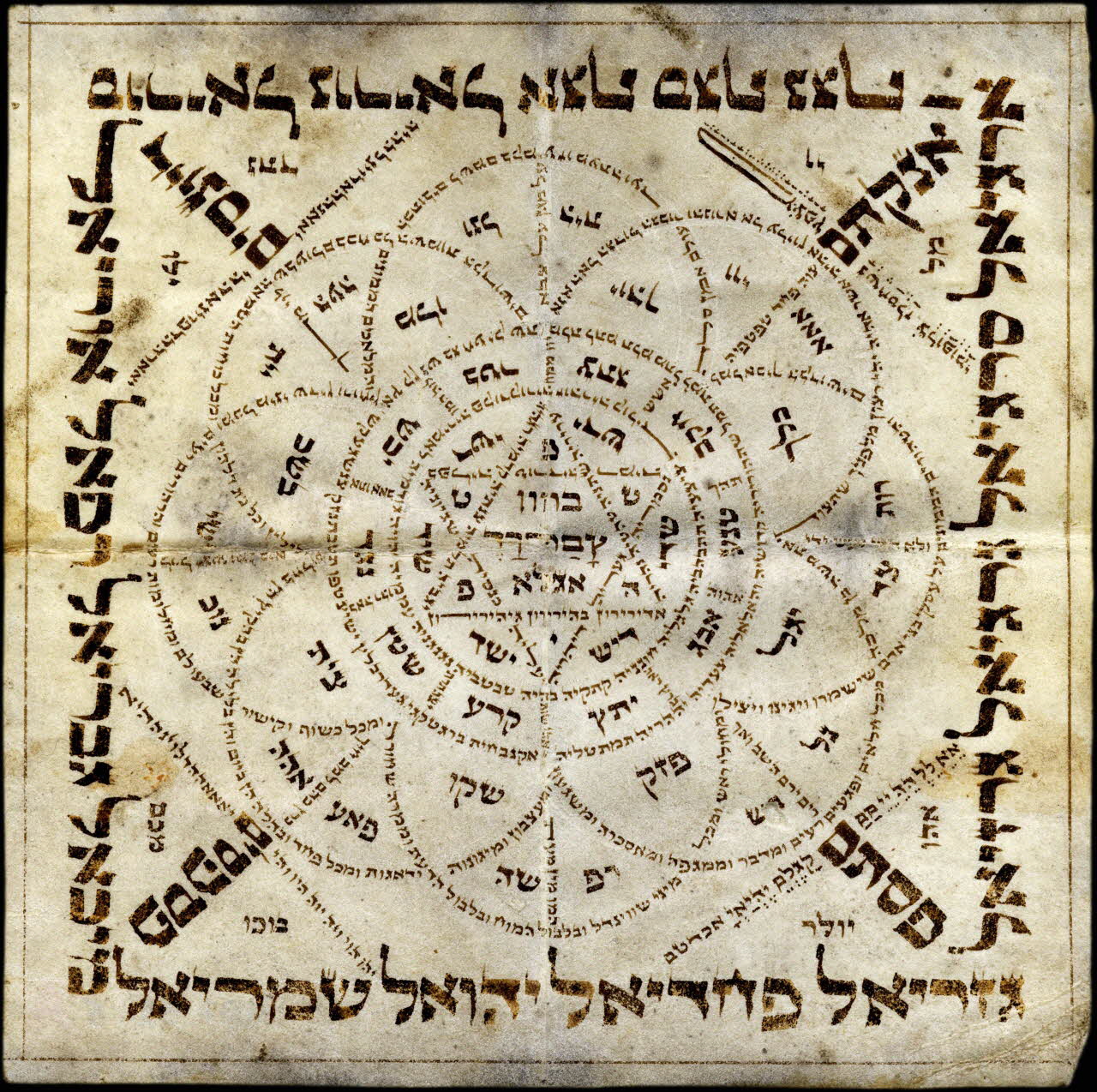

DécouvrirGare aux sorciers!

La magie et la sorcellerie, certains d’entre nous les considèrent comme des superstitions risibles, d’autres y croient, beaucoup hésitent. Mais y croire a mauvaise réputation auprès des esprits forts: les croyances, c’était bon pour nos ancêtres et surtout à la campagne, ou c’est encore bon pour les pays en voie de développement—en tout cas pas chez nous, pas aujourd’hui et certainement pas en ville. Pourtant l’observation des comportements de nos contemporains montre que les progrès de la science n’ont pas marqué la fin des mystères et des croyances, ni dans la France post-industrielle ni ailleurs. Souvent impuissants face au malheur, la souffrance, l’angoisse, les hommes ne se contentent pas des réponses apportées par la science. Celle-ci laisse une place apparemment irréductible à d’autres principes et d’autres systèmes de représentation du monde. Découvrir

DécouvrirAbécédaire insolite!

Que font ces objets au Mucem ?

Comme l’indique son nom, le Mucem est un musée de civilisations. C’est-à-dire qu’il s’intéresse à tout ce qui est produit et utilisé par les sociétés européennes et méditerranéennes, depuis la naissance de l’humanité jusqu’à nos jours. À ses yeux, une sculpture funéraire de l’Egypte Antique parle autant des pratiques rituelles autour de la mort sous le règne des pharaons qu’une couronne de fleurs en perles de verre raconte l’attachement aux défunts dans la France de la première moitié du XXe siècle.

Chaque objet, aussi modeste ou kitch soit-il, témoigne donc de la société dont il est issu. C’est pourquoi le musée, depuis sa création, s’est donné pour mission de rechercher et de conserver une grande variété des témoins possibles et imaginables afin d’en garder la mémoire. Il a en particulier œuvré d’une manière systématique en organisant chaque année des enquêtes collectes. Pour un thème donné, dans un espace géographique délimité, les chercheurs du Mucem recueillent paroles, images et objets. C’est ainsi que les artefacts ci-dessous ont trouvé le chemin des collections nationales.

Voici une sélection, sous la forme ludique d’un abécédaire, de certaines des œuvres les plus insolites conservées par le Mucem, ainsi que les arguments plaidant en faveur de leur entrée dans le patrimoine européen et méditerranéen du musée. Découvrir

DécouvrirDes plages de Californie au Mucem : La culture skateboard au musée

José de Matos, Tony Hawk, Mark Gonzales… ces noms, qui parlent à tous ceux et toutes celles qui ont un jour skaté, sont ceux de skateurs historiques présents sous plusieurs formes dans les collections du Mucem. Certains d’entre eux ont donné des skateboards, des équipements ou des souvenirs aux musées, tandis que d’autres sont évoqués grâce à des skateboards griffés à leur nom. Découvrir

DécouvrirDessine-moi un lion

L’art animalier de Gustave Soury

Gustave Soury (1844—1966) est un dessinateur, peintre, affichiste et publicitaire qui s’est spécialisé dans l’art animalier à destination des cirques et ménageries foraines.

Son œuvre gigantesque et minutieuse, dominée par la figure des grands fauves, témoigne de sa passion, mais aussi de la fascination de notre société urbaine pour les animaux exotiques, leur sauvagerie effrayante et leur intimité attendrissante. Découvrir

DécouvrirDu café

Le café (qahwa en arabe, terme aussi employé pour désigner le vin) nous est parvenu par le monde arabe et ottoman. Depuis les plateaux d’Abyssinie, où la culture du caféier est attestée au XIIe siècle, le café traversa la mer Rouge pour être d’abord cultivé sur le littoral de «l’Arabie heureuse» (Yémen actuel) puis sous les climats tropicaux des territoires des grands empires coloniaux à partir du XVIIe siècle. Appelé le «breuvage du diable» en raison de la couleur noire de son marc, dans lequel on pense pouvoir lire l’avenir, le café a parfois été discrédité par les médecins pour ses effets néfastes sur la santé (boisson jugée antiphysiologique et addictive).

Aujourd’hui, le café est la deuxième boisson consommée le plus au monde après l’eau, mais toujours en concurrence avec le thé.

Les riches collections du Mucem associées au café témoignent des différentes manières de préparer et de consommer cette boisson depuis le XVIIIe siècle, dans l’espace domestique et dans l’espace public. Elles évoquent aussi les lieux de sociabilité que sont devenus les cafés.