I

Mucem (M.)

The exhibition extends far beyond the borders of the Mediterranean…

Jean-Marc Besse and Guillaume Monsaingeon (J-M. B. et G.M.)

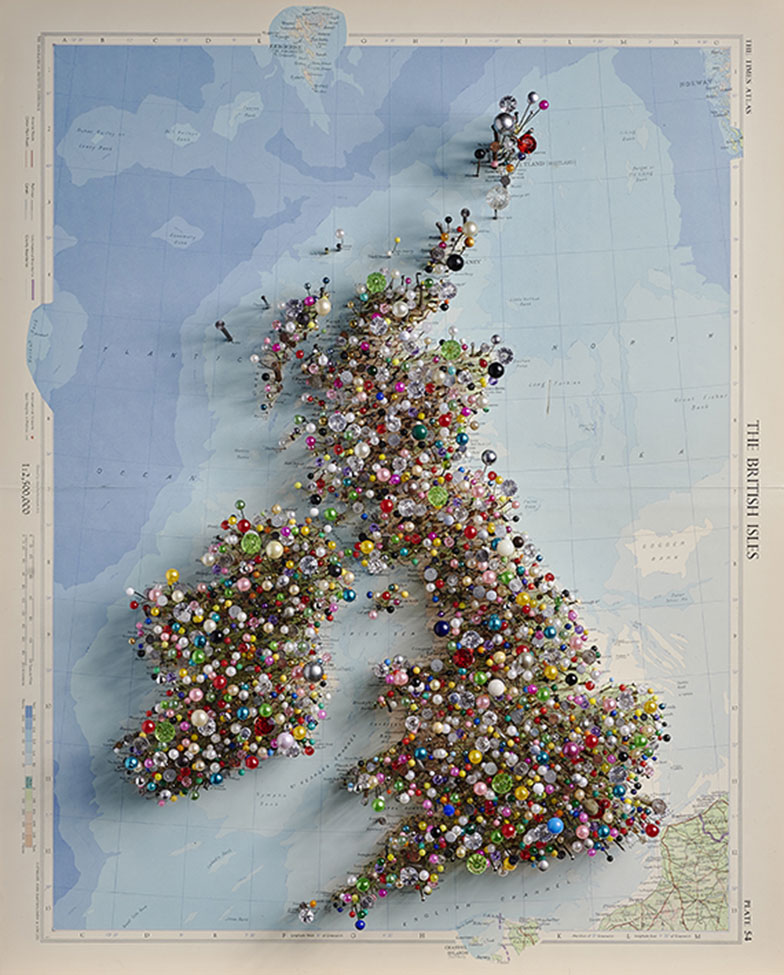

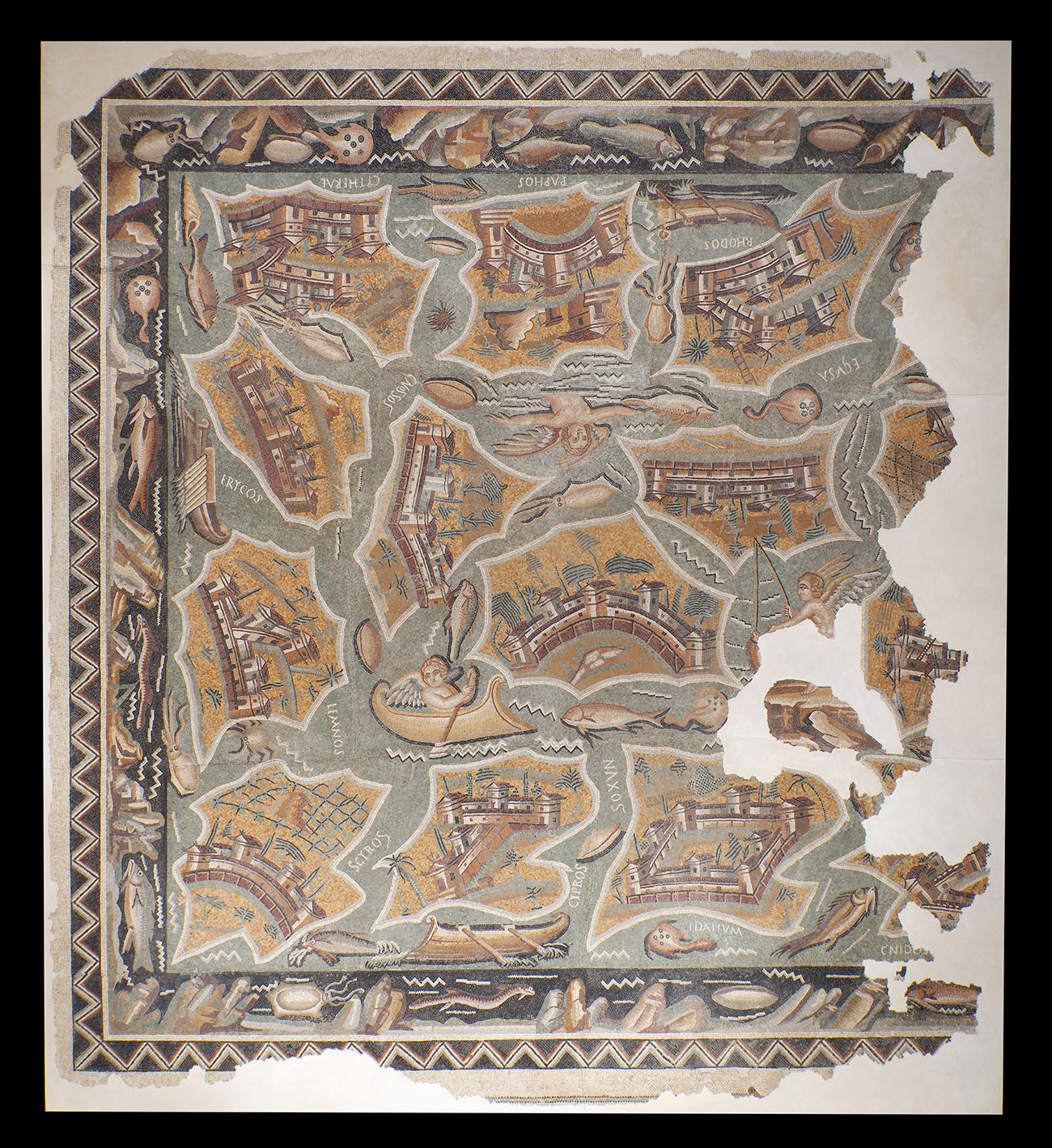

It was important for us to show that beyond the Mediterranean, the question of islands characterizes all areas, starting with the Pacific Ocean, which covers about a third of the total surface area of the globe, and which today accounts for its most important economic exchanges. This does not, of course, prevent us from highlighting the strength of the Mediterranean region. We are opening the exhibition with a masterpiece from the 4th century, on loan from Tunisia: a mosaic that represents in its own unique way this marine world. And the figure of Ulysses hovers over the whole exhibition: this hero who moves (even against his will) from one Mediterranean island to another, is a counterpoint to Robinson Crusoe – the man who remains on a single island.

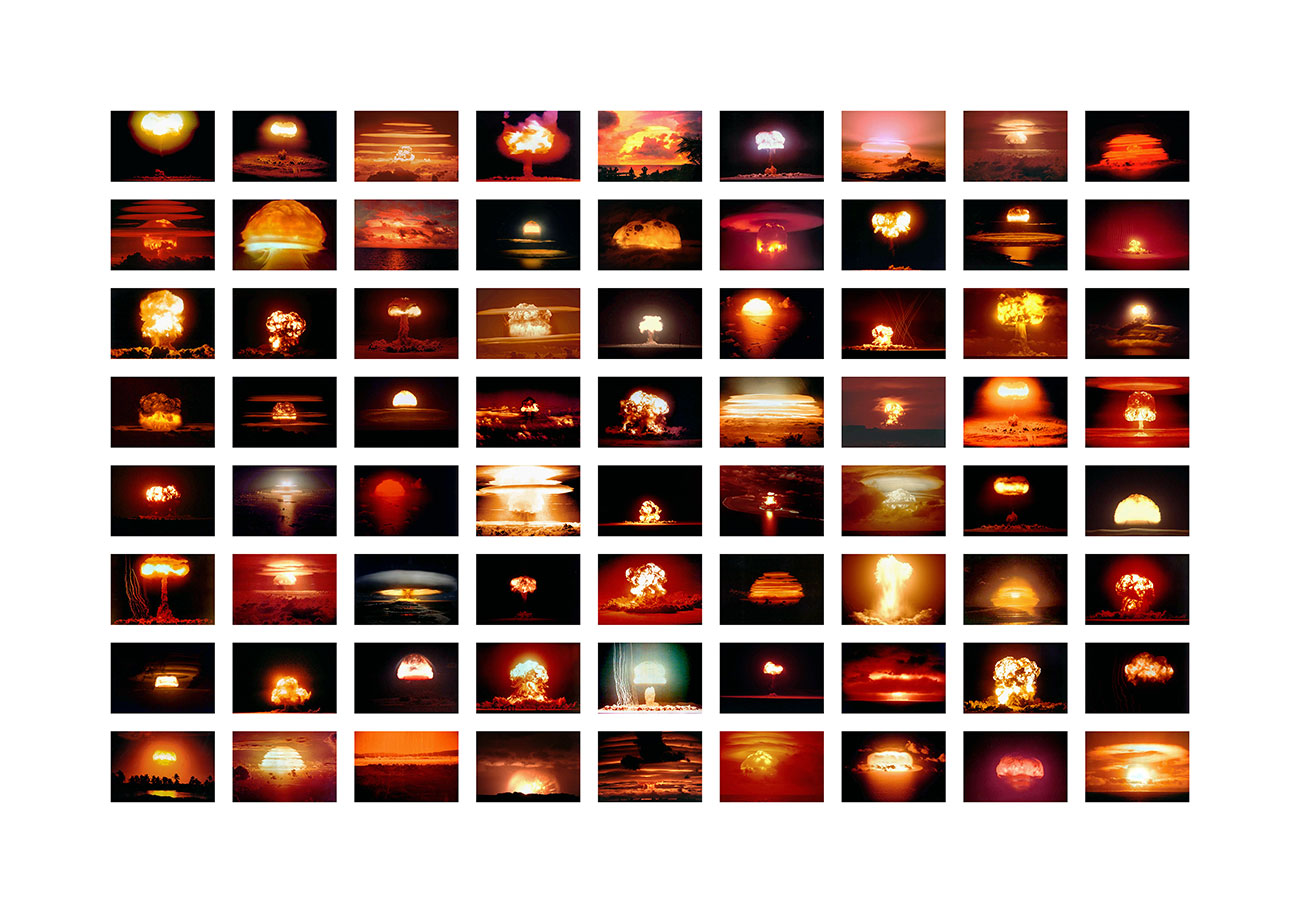

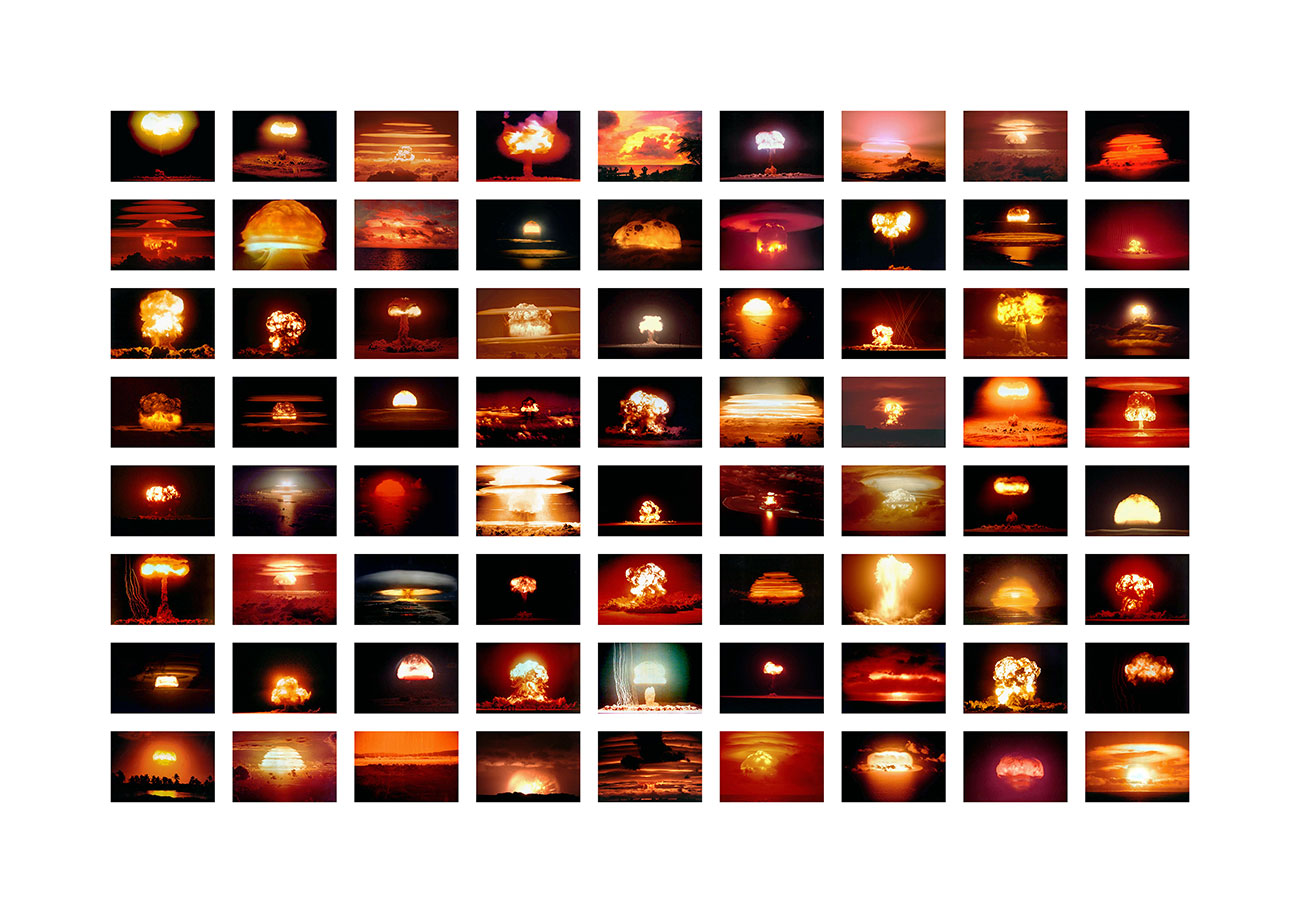

In reality, our approach is neither exotic nor geographical; we do not favour the Mediterranean or any other area. Most of the time, we deal with a specific theme from such or such an island. The emergence of plant and animal species, for instance, is addressed with the help of Madagascar. And military conflicts are addressed both through Malta, the Spratly Islands in the China Seas, and nuclear explosions in Oceania.

M.

The exhibition deals just as much with real islands as imaginary ones…

J-M. B. and G.M.

Yes, indeed! It is even a central point: we want to show how the reality of islands exists just as much in the imaginary as in the economy, and in geopolitics just as much as in art forms.

This year we celebrate the 300th anniversary of Robinson Crusoe. Daniel Defoe’s work was an immediate success. It has been imitated hundreds times. Marx, Rousseau, Virginia Woolf, Borges – everyone has written about this story that has shaped mythologies and modern realities. Who can believe that this book is only fictional, when it has shaped the behaviour of soldiers at war, reality TV fans, and holidaymakers equally?

Islands are much more than a metaphor or a fashion; they are a way of addressing everyone.

The Romans, who knew about cities, immediately referred to them as “urban islets”. This is not a decorative image; it is a way of showing that space is built in archipelagos and islands. Through islands, we underline that nothing in space is either totally isolated nor part of a complete continuum. Islands help us to think about the faraway, yet also about our everyday.

M.

So it is a question of broaching islands as a “magnifying mirror” that allows us to understand our world?

J-M. B. and G.M.

The third section of the exhibition is devoted to contemporary geopolitics. We hear every day about islands that are tax havens, shelters and migration traps. Islands are often mentioned in connection with environmental threats, or even the risk of conflict: we believe that islands, often small and unknown, must be better understood in order to decipher a complex and often violent world.

M.

In what way are islands a major geopolitical issue today

J-M. B. and G.M.

Beyond a direct military confrontation (the Third World War could well break out in the China Seas, around the Spratly Islands), the stakes are economic. We seek to explain, for instance, how with the help of tiny islets lost in the ocean, the US and France have respectively carved out the world’s first and second largest maritime domains known as “exclusive economic zones” (EEZs): an island like Clipperton, which measures less than 2 km², produces an EEZ of over 400,000 km² for France. A nice island effect, no? Thanks to islands and archipelagos, France claims an EEZ of almost 10.7 million km². Coincidence: in 1907, the French colonial empire at its peak was estimated to stretch across 10.4 million km²… Islands had little to do with this at the time, but they have become key players. Until recently, the International Tribunal in The Hague had to clarify exactly what an island was and what was meant by “habitable”; none of this is obvious.

M.

What place does cartography occupy in the exhibition?

J-M. B. and G.M.

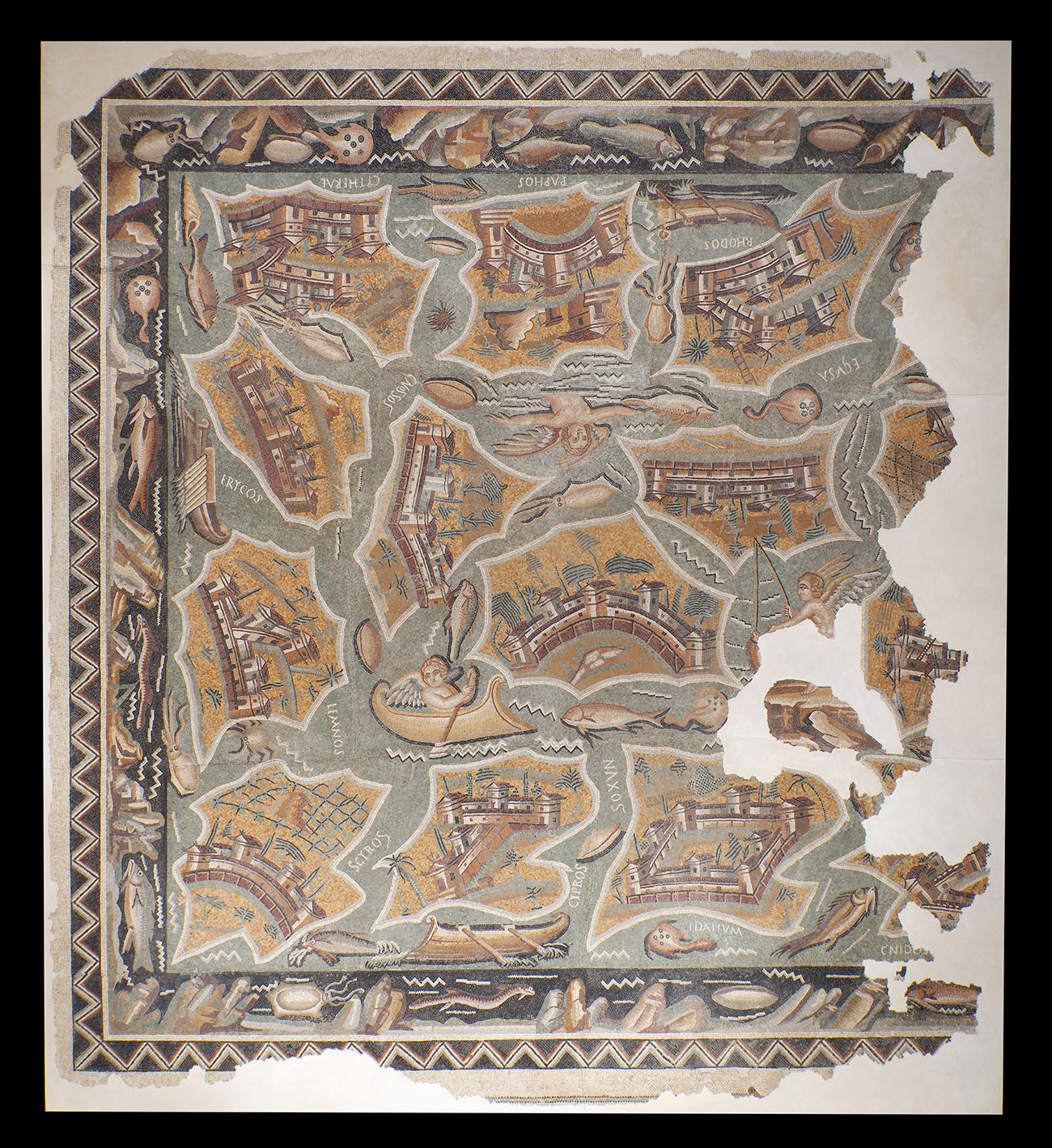

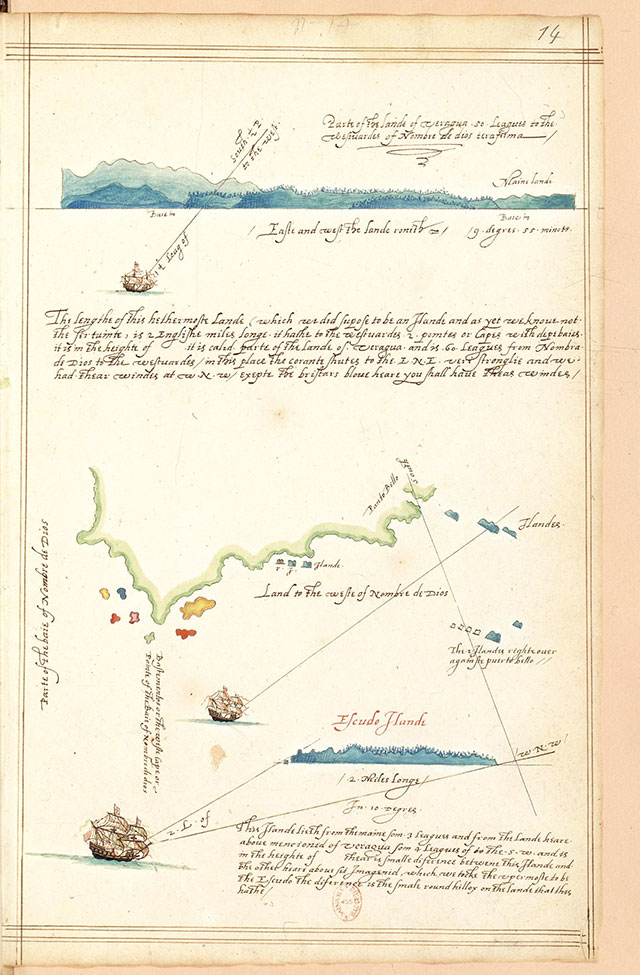

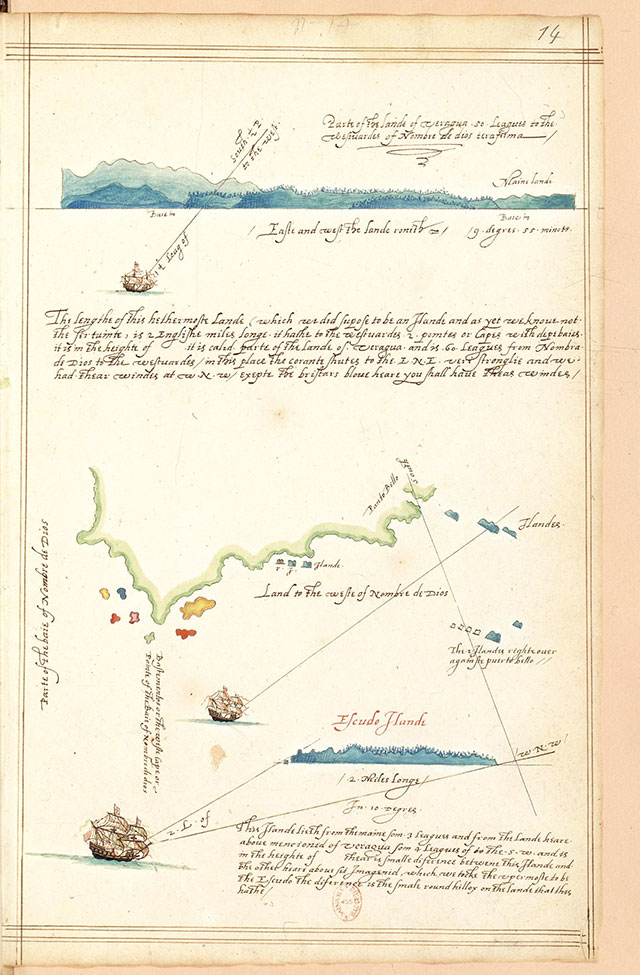

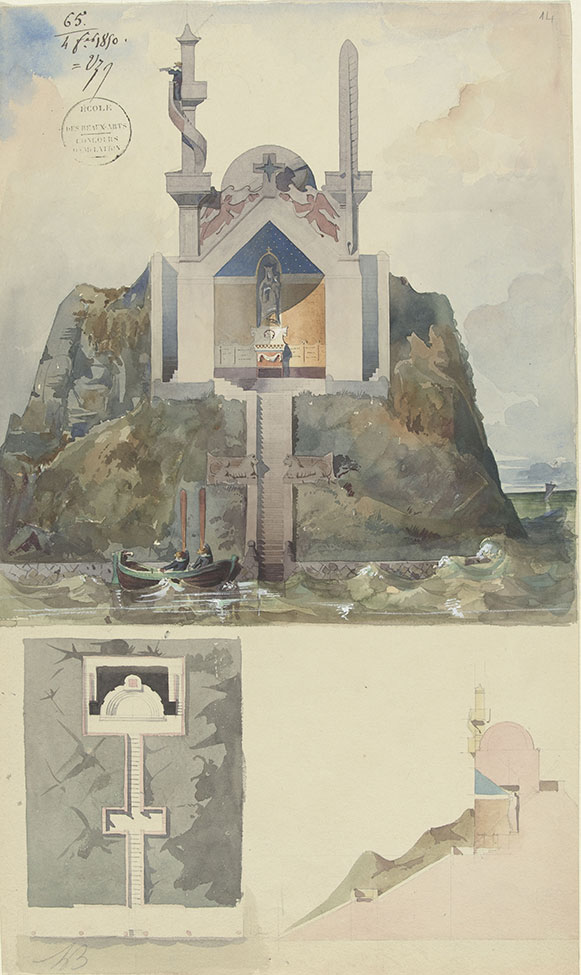

We both met because of our shared passion for maps. But we didn’t want to reduce our project to an exhibition about cartography. For example, the first section is made up of rough profiles that correspond much more to the experience of mariners: they didn’t really know where they were arriving, nor whether it was an island. To show maps from the outset would be to answer the question we had not yet asked.

The maps used in the second section show how islands have contributed to the building of knowledge. The Bibliothèque nationale de France loaned us extraordinary items such as the Miller Atlas and the copy of a map representing the routes of the various navigators around the world that belonged to Louis XVI – a two-metre long document. Marseille Libraries (BMVR) loaned nautical atlases, one of which, though unfinished, clearly shows how the cartographic representation of the Mediterranean was constructed. But we also address school maps; and we have worked with the computer graphics department of newspaper to design maps for the third section. The exhibition therefore presents a varied selection of very original and colorful maps, even though its itinerary is enriched with many other types of objects

M.

What are these other types of objects that can be seen in the exhibition?

J-M. B. and G.M.

Pieces from Asia, such as a vase representing the world as a “Japon-island” and a “rock of scholars” from the Musée Guimet. The Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle and the musée de l’université d’Aix-Marseille, heir of the musée colonial de Marseille, have lent us some rare items. For instance, these include a stuffed lemur nick-named “aye-aye”; it is a very ugly animal, about 50 cm in length. It was quite scary, with its overdeveloped index finger used to scoop up larvae, and this animal only exists on the island of Madagascar. Fortunately, just nearby will be a set of five much prettier, stuffed birds, that highlight how species adapt to an island’s diverse environments.

M.

Beyond its historical and scientific dimensions, the exhibition also gives pride of place to the imagination…

J-M. B.

and G.M.

Yes: cinema, of course, with posters (which always play on these representations) and in particular with a montage of fiction films highlighting the ambivalence of the island in Les Chasses du comte Zaroff, as with in Nanni Moretti (Journal intime) or Jacques Rozier (Les Naufragés de l’île de la Tortue). But also the Roman mosaic already mentioned, a 25 m² masterpiece that presents the Mediterranean islands in disorder: it is an enigma that excites scientists, and we hope that it will intrigue more than one visitor.

The songs are not to be outdone, with Jeanne Moreau and Caetano Veloso: it’s so evocative! We also play with many postage stamps representing islands with the sovereign’s face and the plane that connects the island to the outside world. There are hundreds of them, which express the strength of this link to islands at the other side of the world. The smaller they are, the more they travel and represent an emotional and aesthetic burden.

M.

Contemporary art also plays a key role in the exhibition?

J-M. B.

and G.M.

There are so many artists working on or with islands – and in all mediums. We commissioned several works, including a series from a young video artist, Pauline Delwaulle, who worked with us throughout the project. Together, we selected 18 themes with which she produced “video haikus” – small commas on a loop scattered throughout the exhibition: the tide that distorts the island, the night beam of lighthouses, the uncertainty around the arrival in the mist, etc.

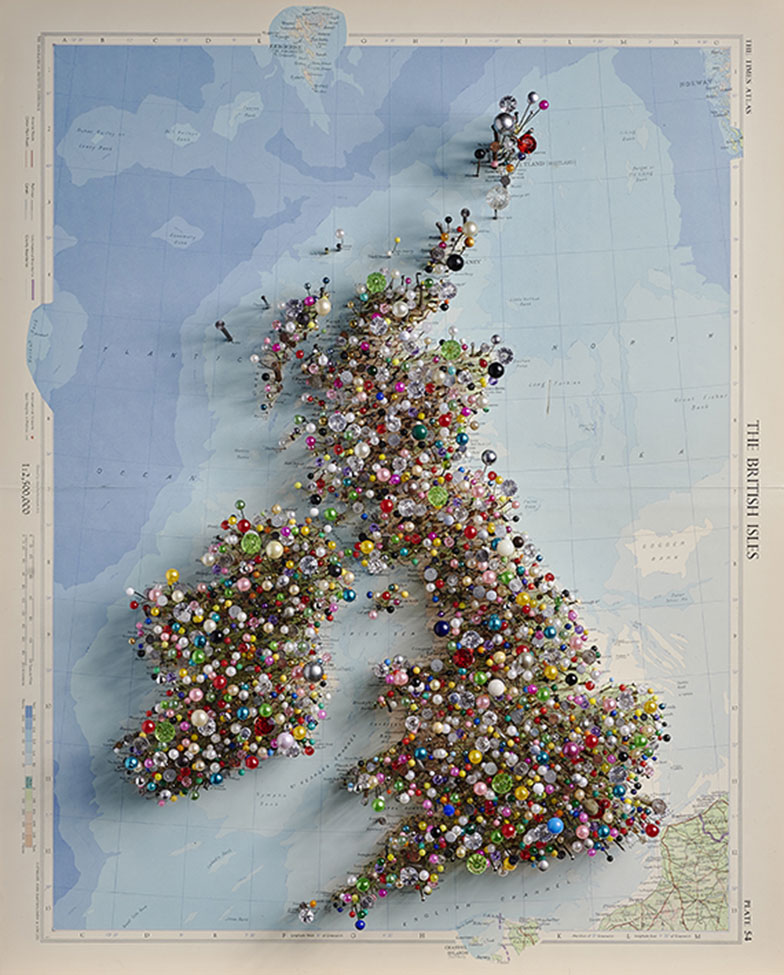

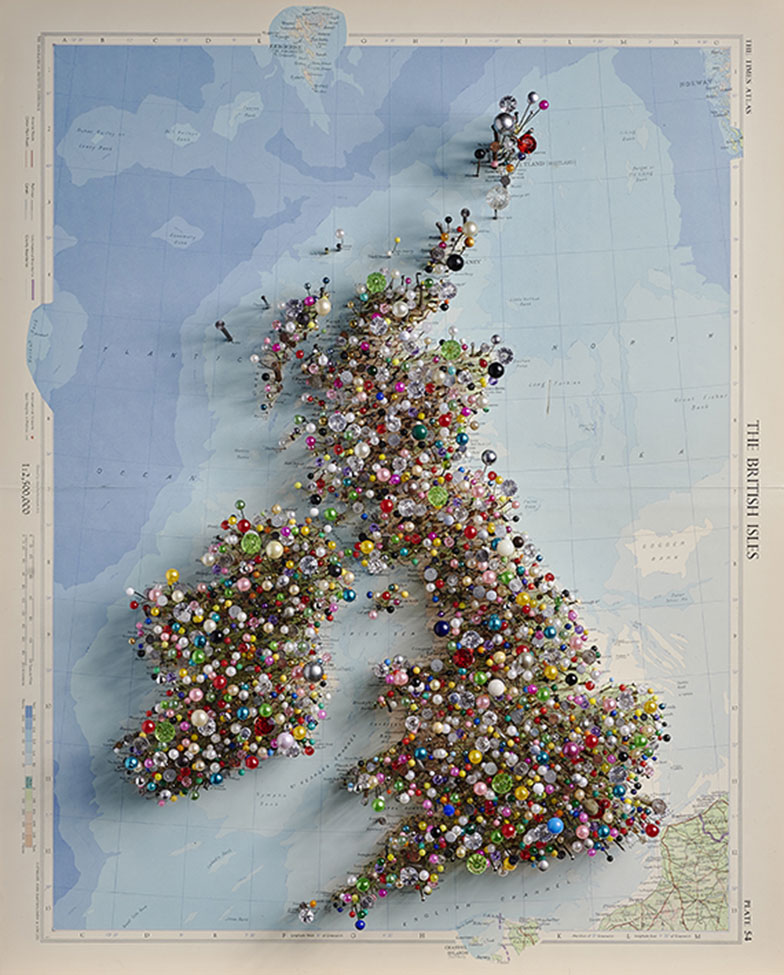

All these artists, often nourished by cutting-edge scientific work, restore the affective and emotional charge of islands. One sees this clearly in the work by Chris Kenny, which is used for the exhibition poster and catalog cover: Fetish Map of the British Isles exudes both love and violence, with the islands crumbling under scrutiny – something that is not lacking in spice.

M.

The exhibition ends with an invitation to set sail for the Island of If with artist David Renaud…

J-M. B. and G.M.

Indeed, we hope to shift the visitor from knowledge to experience of the island. David Renaud was also a travelling companion throughout the project. We commissioned two works from him for the exhibition on the “island effect” in the Pacific. But knowing the work he has been doing for years on islands, we made a proposal to the Centre des monuments nationaux to organize an exhibition of some of his pieces on If. We hope that these fascinating works, combined with the pleasure of leaving the mainland and the charm of the boat trip to If, will be a natural extension to the exhibition.