Giono

Mucem, J4—

Niveau 2

|

From Wednesday 30 October 2019 to Monday 17 February 2020

On the eve of commemoration of the 50th anniversary of the death of Jean Giono (October 2020), the Mucem presents via some 300 works and documents a retrospective that goes far beyond the simplified image of the Provencal writer. Following the progression of his written and filmed work, it reveals his darkness, courage and universality. Giono was a poet who had returned from the mass graves of the First World War and was as committed to describing the depth of evil as to finding its antidotes: creativity, work, pacifism, friendships with painters, nature as a refuge, and escapes into the imaginary.

To flesh out one of the most prolific artists of the 20th century, almost all of his manuscripts, presented here for the first time, enter into a dialogue with many works and documents: family and administrative archives (including those relating to his two incarcerations); items of photographic reportage; press pieces; first editions; annotated books; sound and film interviews, as well as all of the writer's workbooks; films made by him or that he produced and scripted; cinematographic adaptations of his work by Marcel Pagnol and Jean-Paul Rappeneau (not to mention the animated film by Frédéric Back, The Man who planted trees); the naive paintings of the mysterious Charles-Frédéric Brun who inspired him The Deserter; the entirety of his frightening Journal held during the Occupation; and the paintings of his painter friends, including first and foremost Bernard Buffet.

These tangible traces of life and creativity will be doubled up with the symbolic evocation of a matrix experience of the oeuvre entrusted to four contemporary artists. Firstly, there is that of Giono, the simple soldier lost in the maelstrom of war, without which neither the books, the pacifist commitment, the incarcerations, nor the political polemics that punctuate and obscure his progress, logically opens the exhibition with an immersive installation by Jean-Jacques Lebel. Then comes a vision of Provence, far from the folkloric clichés, incarnated via the works of the plastic artist Thu Van Tran and the filmmaker Alessandro Comodin. Finally, the visual artist Clémentine Mélois revisits the library of Giono, this place of freedom and breath, which is at the heart of her life just as much as it is central to the exhibition.

—Curation: Emmanuelle Lambert, writer

—Consultant: Jacques Mény, president of the Société des amis de Giono

—Scenography: Pascal Rodriguez

—Catalogue: a co-publication with éditions Gallimard

As part of the Year of Giono, with the city of Manosque / DLVA

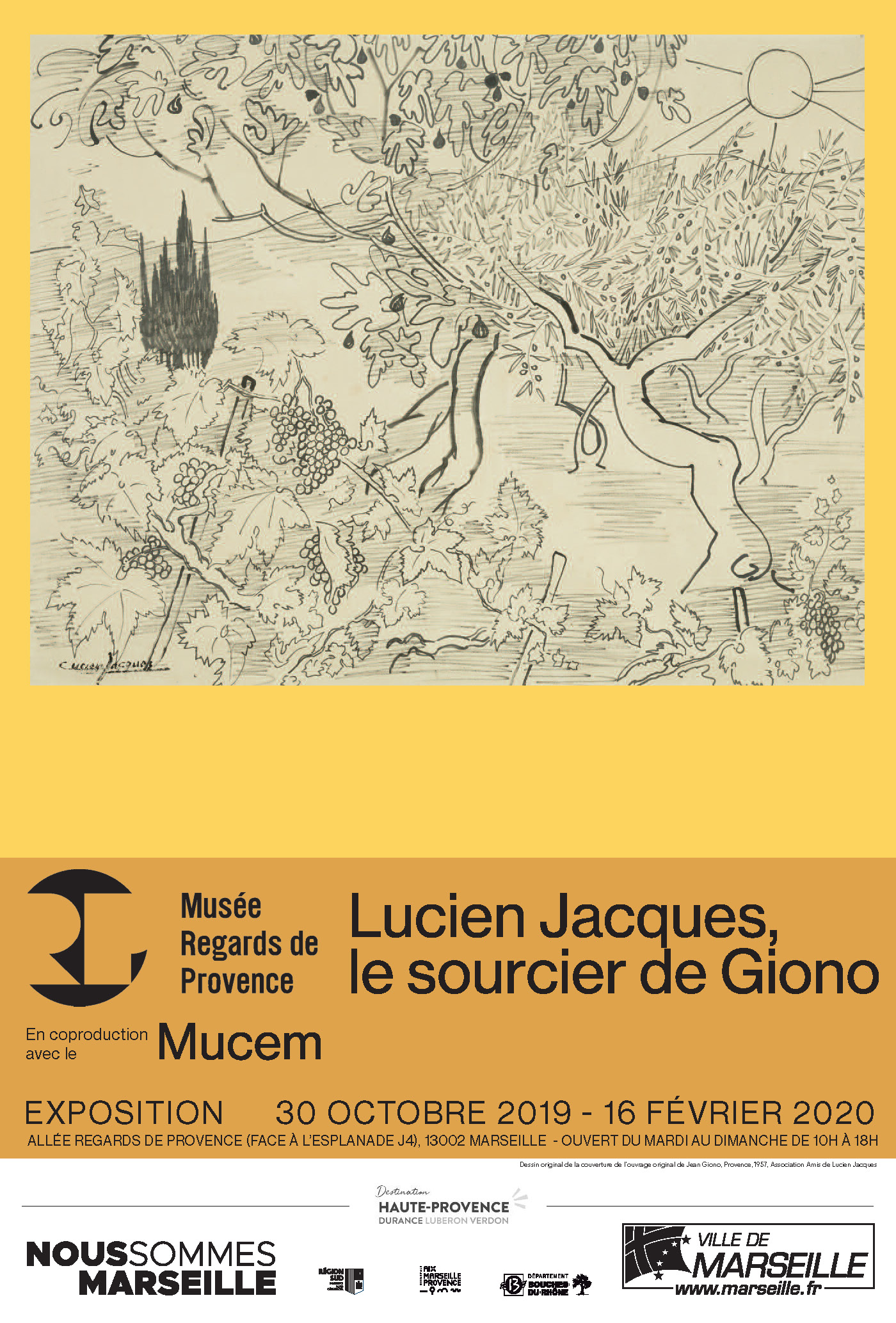

Exhibition at the musée Regards de Provence

« Lucien Jacques, le sourcier de Giono »

From 30 October 2019 to 16 February 2020

—Exhibition curator: Jean-François Chougnet,

—With the support of Jacky Michel, president of the Association des amis de Lucien Jacques

|

Lucien Jacques (1891-1961) has often been read and seen through his unique friendship with Jean Giono. Although this exhibition – which takes place in parallel with the Mucem’s “Giono” exhibition – cannot totally escape this gaze, it nevertheless intends to show an autonomy of Lucien Jacques’s work.

The exhibition is co-produced by the musée Regards de Provence and the Mucem, with the support of the Association des amis de Lucien Jacques and the Durance-Lubéron-Verdon connorbation (DLVA). Practical information A duo ticket to visit the exhibitions “Giono” and “Lucien Jacques” is available for 11 euros. |

Exhibition itinerary

Prologue

“I believe that there is nothing objective, that everything is subjective, and therefore both the reader and the author, the two subjectives, must coincide. At that moment, you have created truth.”

(Jean Giono, Interview with Jean Amrouche and Taos Amrouche)

Designed by writer and exhibition curator Emmanuelle Lambert, the exhibition staged by Mucem is produced with the support of the Association des Amis de Jean Giono. The latter is chaired by Jacques Mény, filmmaker and publisher of Giono, who is the exhibition’s scientific advisor. Scheduled to run between 30 October 2019 to 17 February 2020, it opens the series of celebrations to mark the 50th anniversary of the passing of Jean Giono in 2020.

Jean Giono is an incarnation of the figure of the writer in the 20th century. His novels and stories, their adaptation for cinema, his collaborations with painters and illustrators, his many television interviews and his membership of the Académie Goncourt have made him the heritage author par excellence. Often portrayed as the patriarch of French literature, read and admired, published by Pléiade barely a year after his death and taught from college to university, he is today assigned to controversial-free posterity, precipitated by stylistic grandeur and Provencal sweetness. Between this image of Epinal and Giono’s work, however, there is a gigantic gap. Since his first stories and political commitments, everything has been marked by an obsession with violence and battles, starting with the celebration of nature and the simplicity of rural life, born from the trauma of the First World War, for which he was called up aged 20. The failure of pacifist endeavours, the periods of incarceration and suspicions of collaborationism during the Second World War contributed in turn to nourish a darkness that can be found in the two new periods of his work in the post-war years – the Romantic Chronicles and the Horseman Cycle.

Giono’s persistent image as a Provencal writer or, for the more cautious, as a “writer of Provence” illustrates one of the most immediate expectations of such an exhibition in such a place. To this, we will add the figure of the writer sitting at his desk in Manosque, wrapped in his blanket, with a pipe in his mouth and speaking in song. Giving Giono back what is due to him imposes the need to be rid of an idea: Provencalism, whether it be that of Marcel Pagnol or that of Frédéric Mistral, is not only one of his explicitly formulated hates, but also goes against the meaning of his books. Giono’s Provence does not exist any more than Faulkner’s South. Where this misinterpretation and its clarification ideally meet the objective of this exhibition is that Giono gives literary practice its due: rarely has an author demonstrated so ostentatiously (“the immobile traveller”) that literature is above all a double practice, of reading and writing, and that Giono’s Provence, a graphomaniac and bulimic reader, is what is articulated between the outside world around him and his library – what is seen, said and written.

The exhibition will play on these differences, both the a priori and the expected. They must be taken against the grain so that the exhibition can deliver what one would expect from a literary proposal, namely a reading: reading the path of the work, the author’s figure built by Giono over the years, and the creative process are all paths that those made by the visitors to the exhibition will enrich, nuance and thwart, in a journey whose structure is chronological, yet within which setbacks may occur, particularly to give full place to the literary imagination.

The latter can hardly be shown directly or literally. It is supported here by four artists who are creating a work specially designed for the exhibition: Jean-Jacques Lebel, in an inaugural installation, evokes the experience of terror that was the 1914-1918 war; Thu Van Tran, on Provence; Clémentine Mélois, on Giono’s intimate library; and the filmmaker Alessandro Comodin, on what remains of the places, plants and facets of Giono today.

To give back to the Virgilian storyteller Provencal wonders and the novelist a return to Stendhal – that part of flesh and darkness without which his light could not shine: this is the objective of this exhibition, at the articulation of literary history and the creative experience.

Withdrawing from evil (1895-1939)

“I cannot forget the war. I would like to. Sometimes I go two or three days without thinking about it, and suddenly I see it again, I feel it, I hear it, I still suffer from it. And I’m afraid.”

(Je ne peux pas oublier, 1934)

Jean-Jacques Lebel, La révolte contre l’ignoble, 2019 (installation)

The 1914-1918 war is the matrix from which Giono’s work comes out, and the trenches, the place from which a small anonymous young man escaped to become one of the greatest writers of the 20th century. Made of terror and healing through art, this experience is evoked as soon as the exhibition opens, with an installation by the artist Jean-Jacques Lebel.

“Intelligence is to withdraw from evil.”

(Lettre aux paysans sur la pauvreté et la paix, 1938)

When he was conscripted in 1915, Jean Giono was 20 years old. A bank clerk, he left school at the age of 16 to provide financial support for his family that was in difficulty further to the deterioration of his father’s health. He reads a lot, has a passion for poetry and composes short texts. He already loves Élise Maurin, who lives across the street from him in Manosque. Demobbed in 1919, he resumes his life, to which writing figures ever more prominently. If Giono minimised the horrors of war in his letters to his family (which are also subject to military censorship), his work is full of dark visions, natural disasters and killings that are its metaphor, and this since the beginnings of his career as a writer in 1929, with Colline: Giono the writer was born in the trenches, and he seeks to “withdraw from evil”.

In 1931, he finally publishes his great novel about the war: Le Grand Troupeau, a year before Voyage au bout de la nuit by Louis-Ferdinand Céline, also a veteran of the 1914-1918 war. And so he becomes famous. Committed body and soul to pacifist activism, he also advocates a return to rural life styles that oppose the mechanisation and profit-seeking that has led men to their downfall in what was called “the Great War”. His involvement led to his incarceration in 1939, just after France declares war on Germany.

- Jean le Bleu

-

“What I have to say, I write about, the rest is zero.”

(Journal, 16 January 1936)

This room presents a chronology of Jean Giono’s life, several original manuscripts and numerous historical and biographical documents.

Born in Manosque, son of a shoemaker and an ironing maid, Giono describes his childhood in a largely romanticised way in Jean le Bleu in 1932. His first known text, Vallorbe, dates back to his 16th birthday. He wrote it during a stay with his father’s sister. After the experience of the 1914-1918 war, Giono pursued his desire to write, while working at the bank, which allowed him to build a first personal library, nourished by the classics whose influence can be found in all his books. He left his job in the early 1930s, after the success of his first book.Giono’s first three novels – Colline, Un de Baumugnes and Regain – are known as “Trilogy of Pan”. It is a reference to the Greek god of nature. With his entry into literary work, Giono occupies the place of the eulogist of harmony between man and nature, who, if mistreated, takes noisy revenge, but if the course of a life in accordance with the rural environment is resumed, rewards men with abundance, fertility and joy.

In the 1930s, Giono continues and extends the Romance vein in his work, still firmly rooted in a transformed Provence, far from regionalist clichés. The place of man at the heart of the world remains one of his favourite themes, with his heroes facing initiatory trials in the face of elements that are unleashed, and individuals who are drained of life, but who learn to be reborn upon contact with them, accepting fusion with nature.

Louis David was Giono’s great friend from when he was a teenager. Also of modest origin, he had the same love for art and literature as Giono. He was killed during the war from a bullet to the stomach. All his life, Giono kept the little notebook that his friend had given him before conscription.Born in 1897 in Manosque and the daughter of a hairdresser and a seamstress, Élise Maurin became engaged to Jean Giono, her neighbour, on one of the occasions when he was on leave during the 1914-1918 war. They married in 1920, shortly after Giono’s father’s death. For a time a teacher, Élise, who had two daughters with Giono (Aline and Sylvie), was, throughout her life, his greatest support, whether for the daily management of his work, which she largely typed; the trials and tribulations of his love life and family (she took in Giono’s mother and uncle in their old age); or his two incarcerations. She died at Le Paraïs, Giono’s home, at the age of 101 in 1998.

Painter, draftsman, writer and poet, Lucien Jacques discovered Jean Giono through his poems published in the magazine La Criée in the 1920s. It is through him that Giono is published by Grasset. Their friendship lasted until Lucien’s death in 1961. It is nourished by artistic collaborations, abundant correspondence and quasi family ties.

- Giono/Pagnol

-

In this room, several excerpts from films by Marcel Pagnol are screened, adapted from books by Jean Giono: Jofroi, Angèle, La Femme du boulanger and Regain. If Giono did not appreciate Pagnol’s adaptations, to the point of suing him, these highly successful films contributed to his reputation.

- Peace and life

-

“To frantically defend peace and life.”

(Letter to Louis Brun, 1935)

In this room, several original manuscripts are presented in a central display case. On the walls, a set of historical and biographical documents, including numerous leaflets, newspapers and administrative documents, provide a context for his creativity and activism in the 1930s, when Giono, from Manosque, played the role of “teacher of hope” for French and European youth.In the 1930s, Giono is famous and his novels have a considerable impact. As a natural follow-up to the utopia of his great works of fiction, Giono becomes involved in the “Contadour meetings”, which bring together some 50 participants on nine occasions between 1935 and 1939 in Haute-Provence. At the same time, the political situation in Europe, which was becoming increasingly worrying, pushed him down the path of experimentation and pamphlet writing. A committed pacifist, Giono rises up against patriotism, explaining himself in 1937 with a controversial line: “For my part, I would rather be a living German than a dead Frenchman.” Horrified by a probable return of war, he expends a desperate energy to alert the public and political leaders with leaflets, petitions and statements in the activist press. When France declares war on Germany, Giono’s failure to “frantically defend peace and life” was total. A few days later, his pacifism led him to be sent to Fort Saint-Nicolas, the military prison in Marseille, where he was held for two months.

Thu Van Tran, Gris, 2019 (installation)

The image of a Giono, the writer from Provence, is the source of a misunderstanding. If his books are firmly anchored in the reality that surrounds him, he proceeds as all poets do: by extracting from his subject his share of universality and invention. Strictly speaking, Giono’s Provence therefore only exists in Giono’s imagination. To evoke this abstract and transformed dimension of Provence, the artist Thu Van Tran delivers a composition dedicated to its colour and made from pigments collected in the region.

Return to hell (1940-1945)

“Without the help of the poet, we cannot know the path that delivers us from the embrace of hell.”

(Triomphe de la vie, 1941)

Bernard Buffet, L’Enfer de Dante, 1976

The painter Bernard Buffet met Giono in the early 1950s thanks to his companion Pierre Bergé. The two young people having become very close to the writer and settling for a time not far from Manosque, were very influenced by his radical pacifism (Buffet illustrated Recherche de la pureté for an arts publication in the 1950s). In this 1970s series, Bernard Buffet delivers variations on Dante’s L’Enfer, one of Giono’s favourite poets, whom he rereads avidly in the 1940s.

At the beginning of the Second World War, Giono, like all those who had fought in the 1914-1918 war, returns to hell. Pacifist activism, the Contadour utopia and the attempts that opened up a new path were swept away by the return of war. The years of the German occupation of France mark one of the most controversial periods in his life. He remains a prominent figure, participating in some social events in occupied Paris, publishing literary texts in the collaborationist and anti-Semitic press, and lends himself to the game of photographs and interviews. At the same time, he helps people in danger, Jewish people, communists or those who want to avoid the Forced Labour Service. More than ever, and as will be the case until the end, Giono’s remedies are reading, friendships and escape into the imagination, whether through painting, hard work, especially in his theatre, and the return to authors such as the Latin poet Virgil or the American novelist Herman Melville. But political reality cannot be denied: at the Liberation, Giono is again placed in detention, suspected of having been a collaborator. The Basse-Alpes sorting commission concludes that “no charges are brought against him”. However, he is blacklisted by the National Writers’ Council in September 1944, and could not publish. The ban is suspended Jean Paulhan, who will go on to publish the beginning of Un roi sans divertissement in 1947. But the suspicion of collaborationism has followed him to this day

- The Giono dossier

-

“We no longer need terrestrial oceans and monsters that function for all; we have our own oceans and personal monsters.”

(Pour saluer Melville, 1941)Under the Occupation, Giono continues to publish literary texts in La Nouvelle Revue française, now directed by Pierre Drieu la Rochelle; gives interviews to the collaborationist press; and his play Le Bout de la route has a triumphal four-year run in Paris. But it is undoubtedly the pre-publication of the novel Deux cavaliers de l’orage as a series in La Gerbe, a collaborationist, anti-Semitic, pro-Nazi weekly, as well as the photo report for the Wehrmacht Signal magazine, that will led to his arrest at the time of the Liberation. However, the image of Giono, the collaborator, is inaccurate. He never produced an ideological text supporting the regime, and above all, he hid and helped many people, who would provide written testimonies in his favour. The “Giono dossier” is therefore like his Journal de l’Occupation: problematic, complex, and made up of contradictory acts. The bitterness into which his arrest in September 1944 plunges him nourishes the profound transformation of his post-war work, which takes the form of a search for individual happiness as opposed to a past collective activism.

At the time of his incarceration in the Saint-Vincent-les-Forts centre, Giono writes a document for the commission examining his case listing all the support he had provided to people in danger during the Occupation. At the same time, he sends the same document to some of his Resistance writer friends. These actions are corroborated by written testimonies, such as that of Jan Meyerowitz, a Jewish musician whom he had hidden and helped in Manosque, and of Félix Bernard, Roger Bernard’s father, a member of René Char’s maquis.

- Espaces intérieurs

-

“The purest emotions of my life.”

(Virgile, 1943)

This room evokes Giono’s relationship to reading and the rediscovery of the classics, in parallel with the few works written during the 1940s. The intimacy and pleasure of reading is evoked by an installation by the artist Clémentine Mélois, surrounded by display cases presenting original manuscripts and reference books. A photographic montage also covers the walls of the room with important works from the library at Paraïs.

A self-taught writer, Giono left school young and forged for himself a personal and intimate culture. All his life he has bought books, and a large part of his house in Manosque is covered with library furniture and shelves. His passion for poets and writers is reflected in the influences that are perceptible in his own books, which include memories of Don Quixote as well as William Faulkner, and La Chartreuse de Parme by Stendhal, which he had in his jacket after the 1914-1918 war, as well as Virgil, Dante and Homer. He also seized on this culture to become a writer for others: among his most beautiful texts are his Virgile (written in 1943) and Pour saluer Melville (1941), a tribute to the author of Moby Dick, which he translated in 1939 with Lucien Jacques and Joan Smith, an English friend. He will continue the exercise in the post-war period, in particular with his preface to Machiavelli’s correspondence, “Monsieur Machiavelli or the human heart revealed”. - Out of this world

-

This room presents an immersion into Giono’s writing ritual: his many workbooks, fully exhibited, are surrounded by the very many works gifted by his painter friends, hung on the room’s walls.

Élise Giono and her daughters, passing friends at their home, occasional visitors, and Giono’s interviews and diary all provide the same testimony: the daily life of Le Paraïs took place to the rhythm of Giono’s writing sessions, who had the premises designed to expand the area of his office and library even further. This relentless worker has produced a very large body of work. He recorded his ideas, plans and projections in small spiral notebooks, prior to the beautiful manuscripts written in ink in regular handwritten script, almost all of which he carefully preserved. Surrounded by the works of his many painter friends (Ambrogiani, Buffet, Berger, Fiorio, Jacques, Parsus, Soutter, etc.), Giono’s writing ritual is both anchored in the most material of life, and as if withdrawn from the world, the joys and pains of an imaginary one.Clémentine Mélois, Un cabinet d’amateur, 2019 (installation)

Giono reads as he breathes. An outstandingly popular writer, stylist and an author of a work at the crossroads of common culture and erudite culture, he has adopted in the first instance the great points of references of Art History, literature and painting. To approach this intimate relationship, made of pleasure and dwelling on matters, the artist Clémentine Mélois proposes a playful, poetic evocation of his library and the works that structure his imagination.

“Works of art in museums” (1946-1970)

“He’ll only stop to die.”

(Le Déserteur, 1966)

Six years before his death, Giono is approached by the Swiss publisher René Creux, who has just discovered the work of a mysterious painter who had lived in the 19th century in the canton of Valais, where he was nicknamed “The Deserter”. An author of hundreds of modest portraits resembling ex-voto portraits, Charles-Frédéric Brun offers Giono the figure for one of his last books, a character withdrawn from struggles and life.

After the bitter failure of his political activism, his two incarcerations, and the publication ban that hits him at the time of the Liberation, Giono deserts the subject-matter that was that of his pre-war work and reinvented everything, to return into the light and never to leave it. From now on, he looks at people as if from afar, from an overhang in time and space (“He was only interested in people as objects of art in museums”, he writes in Le Bonheur fou in 1957). This renewal of his work follows three main paths: that of the Romantic Chronicles, a series of novels and harsh narratives, marked by miscellaneous fact, and whose most emblematic book is Un roi sans divertissement; that of the Cycle of the Horseman, projected in the past, intertwining adventures in Italy and France; and lastly, that of the film industry, which occupies a Giono that is concurrently producer, screenwriter and director. When he dies at home on the night of 8-9 October, 1970, Giono has become what he had been at the beginning: a prolific and acclaimed writer.

This change in the way creativity is expressed is signified by a radical change in the exhibition’s scenography. There are no longer strictly speaking “rooms”, but rather moments inside a spiral where everything is intertwined. The third and last part of the exhibition is a circle that weaves the three threads of Giono’s post-war creation: cinema, the Romantic Chronicles and the Cycle of the Horseman.

- Images

-

The walls are lined with a graphic montage that evoke the creative proliferation around cinema and Giono’s films, projected on a large screen, guiding the visitor’s progress in the central corridor.

It was thanks to a commission from Électricité de France that Giono, who had just finished an intense period of literary work, turned to cinema. L’Eau vive was originally intended to be a documentary about the construction of the Serre-Ponçon dam in the southern French Alps. It was transformed into a film directed by François Villiers, screened at the Cannes Film Festival in 1958. Some time later, Giono created his production company and directed Crésus (1960), with Fernandel. He will entrust the adaptation of Un roi sans divertissement, which required him to do a considerable amount of work to cover his novel, to the director François Leterrier. Just as the book is one of his undisputed masterpieces, the film, released in 1963, is one of the most beautiful achievements of Giono’s cinema, nourished by a colossal work of writing, and by an imagination rooted in painting, particularly that of Bruegel, one of the painters who most influenced him.

- Chronicles

-

Dark and merciless, the novels of the Romantic Chronicles cycle are a scalpel reading of the human soul. Fuelled initially by his readings of Machiavelli and Faulkner, Giono offers a merciless picture of human relationships. They are articulated around the notions of crime, greed and boredom (thus the title of his masterpiece is borrowed from Pascal: “A king without entertainment is a man full of misery”). His taste for darkness and the miscellaneous fact found another place of expression when, in 1954, Arts magazine asked him to cover the trial of Gaston Dominici in Digne, which then fascinated the whole of France: in the old man accused of murder, Giono found “his” farmers. Two years earlier, Orson Welles was also in Digne to make a documentary on the case, which had not yet been completed. Excerpts are projected against the manuscript of Giono’s Notes on the Dominici case.

- Legends

-

The figure of Angelo Pardi, who gave rise to the Horseman Cycle novels, appeared to Giono in 1945. It offers him the pretext of a saga, initially conceived as a long cycle of ten books playing between periods and countries, from the 19th century of his grandfather to the 20th century of his grandson, following the adventures of his main characters between France and Italy. First explored in Mort d’un personnage, this Romance vein inherited from Stendhal led Giono to win back his readers with the publication of The Horseman on the Roof in 1951, then Le Bonheur fou. Giono’s constant interest in history is also reflected in the publication of his only book in a historical collection, Le Désastre de Pavie – and here again he is in Italy, this time in the Renaissance, with the great battle between Francis I and Charles V. He explains this in a 1963 interview with Pierre Dumayet.

Alessandro Comodin, Fleurs blanches, 2019 (30 min; 2K / 1:1,66 - stereo sound; with Paul Bégou and Blanche Caille)

These two windows enclose a projection room where the artist’s commission, which was passed on to filmmaker Alessandro Comodin, will be shown. With a nod to the adaptation of The Horseman on the Roof by Jean-Paul Rappeneau (1995), an excerpt of which is broadcast on the big screen at the end of the central corridor, the visit ends with an opening: the one on Frédéric Back’s animated film, L’Homme qui plantait des arbres, adapted from Giono’s tale in 1987 and screened in its entirety.

Partners and sponsors

With the support of Mutuelles du Soleil

In association with the association des Amis de Jean Giono.

In collaboration with Région Sud Paca and the Ville de Manosque / DLVA

As part of the Year of Giono 2020

In partnership with France 3 Provence-Alpes Côte d'Azur, France Bleu Provence et France Culture